Blog

Jan

School Nutrition News: D.C.-area students owe nearly half a million in K-12 school lunch debt

PCS RCS 0 comments School Lunch News From Around The USA, Uncategorized

WASHINGTON POST: As students in the Washington area went home for winter break, a substantial number were in debt — to the school cafeteria.

Students in the Washington area owe nearly half a million dollars so far this school year in “lunch debt,” according to an analysis by The Washington Post. These are K-12 students in public schools who did not have enough money to pay for meals in their school cafeteria, so they racked up debt to eat.

In some cases, students who cannot pay for lunch are denied hot food and handed a cheese sandwich, according to policy in numerous school districts across the country, including in Prince George’s County Public Schools.

The National School Lunch Program, established in the 1940s, pays free and reduced-cost lunches for millions of U.S. students, but the debts make clear some students still aren’t getting by.

School lunch debt in the Washington area ranges from about $20,000 in the Alexandria City Public Schools to $127,000 in D.C. Public Schools. Tens of thousands of students in the six public school districts in and around the nation’s capital are in the red, according to district officials.

Debt per student varies greatly. In the 161,000-student Montgomery County Public Schools, officials said about 11,000 students have accumulated $80,000 in meal debt so far this school year. That works out to an average of about $7 a student, the equivalent of about three lunches, but officials said that figure can be misleading, as many students have small amounts and then a few have large negative balances.

Teachers, principals, cafeteria workers and poverty experts describe a hidden crisis. And the problem isn’t confined to the D.C. area: Seventy-five percent of U.S. school districts have unpaid student meal debt, according to a survey of 1,550 districts nationwide by the School Nutrition Association, the national organization of school nutrition professionals.

Prince George’s County Public Schools has $24,000 in total meal debt outstanding. In Northern Virginia, Arlington Public Schools has more than $100,000, and Fairfax County Public Schools has more than $110,000.

For a child to qualify for free lunch under the National School Lunch Program, a family of four must make less than $32,630 a year. That amount is the same for all states (except Alaska and Hawaii), which puts kids in high-cost regions such as the D.C. area at a disadvantage over those in more rural areas.

“Every time I see the free-lunch application, I say a little prayer thanking the Lord I don’t have to fill it out,” said Diane Pratt-Heavner, spokeswoman for the School Nutrition Association. “It’s a complicated form that asks a lot of personal information, so I understand why immigrant families don’t complete it.”

Many students in debt belong to families who earn slightly too much to qualify for free meals, or whose parents or guardians fail to complete the free-lunch paperwork, which must be done annually, according to interviews with 11 Washington-area school officials.

| SCHOOL DISTRICT | TOTAL MEAL DEBT (YTD) | TOTAL ENROLLMENT | % RECEIVING FREE AND REDUCED MEALS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montgomery County Public Schools | $80,000 | 161,460 | 34% |

| Prince George’s County Public Schools | $24,000 | 132,322 | 64% |

| Arlington Public Schools | $100,225 | 28,020 | 29% |

| Alexandria City Public Schools | $20,098 | 15,737 | 61% |

| Fairfax County Public Schools | $110,428 | 188,018 | 28% |

| D.C. Public Schools | $127,000 | 48,144 | 77% |

A family of four earning less than $46,435 but more than the free-lunch limit would qualify for reduced-price meals. There is also a special program for the nation’s most low-income schools in which all students automatically qualify for free lunch if more than 40 percent of the student body comes from homes on food stamps or welfare.

School leaders said some immigrant families are fearful to return the free-meal application after the Trump administration announced plans in September to make it harder for immigrants who receive public benefits and are “burdens on American taxpayers” to obtain green cards or permanent residency status.

The high debt burden puts some schools in a gut-wrenching position in which school policy dictates that cafeteria workers are instructed not to give hot food to a child and to offer an “alternate meal” instead, usually a cold cheese sandwich. Lawmakers and anti-poverty activists have dubbed this practice “lunch shaming,” because other students notice what’s going on.

“We don’t want to see a kid get a ‘shame sandwich,’ ” said Michael J. Wilson, director of Maryland Hunger Solutions. “We know good meals help fuel kids’ brains and helps with attendance.”

Montgomery County stopped serving alternate meals in November. But some other Maryland school districts still do, including Prince George’s County.

Schools in Prince George’s have tried to make the process as dignified as possible for students in this situation by trying to “prevent any embarrassment in the lunch line due to lack of funds.”

“Cashiers will no longer take a tray from a student,” Prince George’s County Public Schools policy states. “The alternate meal will be distributed to the student before lunch to avoid the student going through the serving line.”

Virginia outlawed the practice earlier this year, barring schools districts from singling out students who can’t afford to pay for lunch by making them do chores or putting wristbands, stamps or other markers on children. The law effectively stops Virginia public schools from serving alternate lunches, because that is another way of singling kids out. D.C. Public Schools also do not serve alternate meals.

Many D.C. public schools give all students free lunch because the school’s student body meets the high-poverty criteria, but about a quarter of the city’s schools still charge students and have unpaid meal debt.

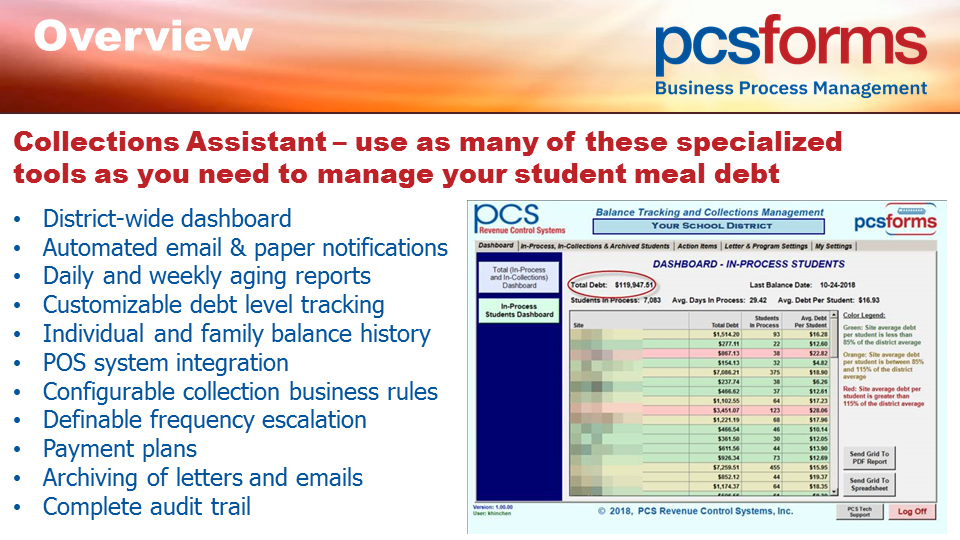

Districts are growing more aggressive at sending letters, emails and texts and calling parents when a child has a negative balance, according to their policies, so that schools are not left paying off the remaining debt at the end of the school year.

School districts sometimes withhold report cards or student records of students with outstanding meal debt. Some districts allow the debt to carry over from year to year, while others don’t.

Schools are caught in a hard place — they don’t want children going hungry or feeling ashamed, but they don’t have extra money to cover the debts, and they want to make sure parents who can pay are paying.

The new tactic many districts are taking is to aggressively seek community donations to help pay off student meal debt. More than half of U.S. school districts are now doing this, the School Nutrition Association found, and D.C.-area schools are part of this trend.

The Montgomery County Public Schools Educational Foundation is trying to raise $300,000 for its “Dine With Dignity” campaign to wipe out lunch debt (the district has $80,000 in meal debt so far this year). The foundation partnered with Starbucks to put information on how to donate on Starbucks cups sold at stores in the district.

“A gentleman walked up to me in a Starbucks store to make a donation because he said when he grew up the alternate meal was a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, and to this day he can’t eat one without feeling sad,” said Yolanda Johnson Pruitt, executive director of the MCPS Educational Foundation. “Kids are entitled to their dignity in the lunch line.”

Business owners and concerned parents are running fundraisers and GoFundMe campaigns to eliminate debt at their local schools, part of a nationwide movement that really took off in 2017 after New Mexico became the first state to ban any form of lunch shaming.

Katie Martin is head of the Parent Teacher Student Association at West Frederick Middle School. As soon as she heard about the lunch debt at her child’s school, she launched a GoFundMe to wipe it out. They have raised about $500 so far, which would cover only a few months.

Black Flag Brewing Co. in Columbia, Md., held a big party on Dec. 23 and donated all proceeds from the event and a GoFundMe campaign to pay off $47,000 of lunch debt in Howard County Public Schools.

“Many people don’t even know this debt exists here in Maryland,” said Brian Gaylor, the brewery founder and an alumnus of Howard County Public Schools. “My teacher friends say they see kids who can’t pay for lunch every day.”

The problem is that the debts come back every year. Ashley D’Amico, who owns a real estate investment company, paid off all the lunch debt in Frederick County Public Schools before Christmas last year, but the debt is back. The Frederick schools’ unpaid lunch balance is currently $8,000, more than double what it was a year ago.

While school district officials acknowledge some parents are forgetful or taking advantage of the system, they think the vast majority of the kids in debt are from financially struggling homes. They report a frequent spike in debt payments every few weeks as families living paycheck to paycheck have money again.

The D.C. Council considered a proposal to give free lunches for all students, but the $2.5-million-a-year cost was considered too high. Maryland passed legislation to cover the costs of all meals for kids who qualify for reduced-price meals starting in 2023, but for now, debts keep amassing.

“Maryland was willing to put up lots of money to get Amazon. We didn’t get Amazon, so we should have some money to spend to feed kids in our state,” Wilson said.

FULL ARTICLE at Washington Post

Tags: School Nutrition News

Contact

Contact